The Virginian Capital is well-centered around the James River, whose sheer significance to the city is ridiculously difficult to overstate. Evidently, Richmond still gets much of its water supply from the river, as it was in the 19th century, when a state of the art facility, the Byrd Park Pump House, was built to provide the city with freshwater. The industrial building has since been long abandoned, yet its remarkable and eerie past still echoes to these days.

The old pump house is located at a secluded section of the James River’s north bank, on the western outskirts of Richmond Downtown. As you reach Pump House Dr, you’ll come across several signs indicating the right direction.

photography by: Omri Westmark

At one point, the road splits into two driveways, the higher of which leads directly to the Byrd Park, where the pump house is nestled. Take note that along its northern side stretches the Dogwood Dell Mountain Biking Trail, which despite its name is accessible also for hikers who can enjoy deep forest paths that are almost always empty and quiet.

photography by: Omri Westmark

The entrance to the park is marked by a couple of info boards, providing interesting facts, maps and regulations for visitors.

photography by: Omri Westmark

After a few meters along the asphalt pathway, the marvelous building looms in the background.

Historically, both the indigenous tribes and European settlers in the area used the abundant springs as their main source of water. It was the exponential demographic growth and the subsequent contamination of most wells that ultimately prompted Richmond to rely on the nearby James River for its freshwater needs.

photography by: Omri Westmark

As part of the city’s endeavor to develop its new source of water, several pumping facilities were constructed along the James River, whereby water from the river would be distributed to almost every neighborhood of Richmond.

Completed in 1883 after two years of construction works, the Pump House was the centerpiece of Richmond’s sophisticated network of waterways. Not only did it serve as the city’s waterworks headquarters, but also as its main pumping station, from where water would be drawn to the uphill Byrd Park Reservoir, and then delivered by gravity to the rest of the city.

photography by: Omri Westmark

The Pumphouse Park is home to three waterways, each of which played a major role in the city’s history. The northernmost canal, known also Tuckahoe Creek is crossable by a newly built bridge.

photography by: Omri Westmark

Created in the 1880’s, the waterway was dubbed as the power feeder canal, as its main function was to power the pump’s turbines that drew water from the James River in the pre-electricity era. Nowadays, the canal is occasionally used for bateau flotillas, a type of motorless wooden boat that was widely used to commute through Virginia’s rivers and waterways between the 17th-19th centuries.

photography by: Omri Westmark

While industrial in nature, the Pump House far eclipses any nondescript facility of its kind. Designed by Winfred E Cutshaw, Richmond’s city engineer at that time, the building is made of granite stones and features a plethora of extravagant elements and ornaments.

photography by: Omri Westmark

Resonating with the Gothic revival-style, the Pump House features elongated lancet windows and Gothic arches, pitched slated roofs, lattice openings as well as gables that protrude outwards, and so, no one will blame you for mistaking this building with a medieval abbey.

photography by: Omri Westmark

Curiously, alongside its mundane role as a water supply facility, the Pump House also served as a prominent venue for high-profile events, hosting some of Richmond’s biggest parties that took place in an open-air terrace, merely few meters above the mechanical gear. Well-dressed residents from all over the city would take a wooden bateau, heading to see and be seen at one of the many social gatherings that made this building far more than just a pumping station.

photography by: Omri Westmark

Unfortunately, its glamorous days were short lived as the pump building ceased all its operations in 1924 and fell into a state of disrepair, whilst its once cutting-edge machinery was scrapped for metal content.

photography by: Omri Westmark

Following World War II, the Pump House was listed for demolition, yet luckily, it was purchased for a measly 1$ by the First Presbyterian Church, sparing it the grim fate.

photography by: Omri Westmark

Over the years, numerous cases of spooky paranormal activity were reported at its premises, in fact, it was classified by several ghost hunters as extremely haunted. One specific reoccurring sight is of Daniel Tetweiler, a person who according to some sources committed suicide inside the building and so, his restless spirit hangs around the edifice ever since.

photography by: Omri Westmark

Despite being closed to the public, urbex enthusiasts and ghost hunters raid the building every now and then. If you can’t control your thrill-seeking instincts, you can try to book one of the rarely offered tours of the building. Alternatively, you can wait until the Pump House will be restored and reopened as there are plans to bring this architectural gem back to its glory days, yet don’t hold your breath since none of which has come to fruition yet.

photography by: Omri Westmark

Tucked away behind the building’s rear façade, the middle waterway is a vestige of the historically renowned project known as the Kanawha Canal. First envisioned by US first president, George Washington, this mega project consisted of a series of waterways that would detour the unnavigable segments of the James and Potomac rivers, creating a seamless passage between the east coast, Richmond’s industrial heartland, the Mississippi River and finally, the Gulf of Mexico.

photography by: Omri Westmark

A lack of funds as well as frequent floods were only some of the reasons why this project was never fully executed, however, an eleven-kilometer-long waterway was constructed parallelly to Richmond’s James River, circumventing the white rapids that make this river unnavigable.

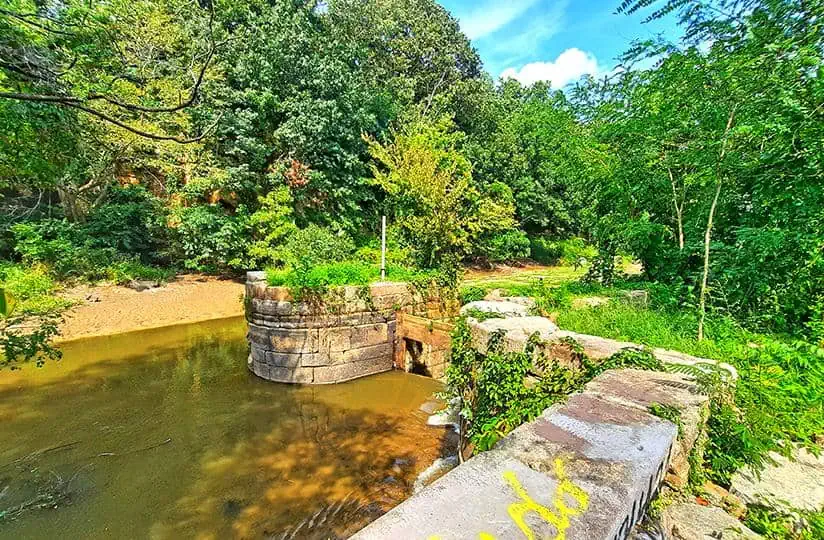

The canal’s two granite covered waterways around the Pump House are in fact locks, used as a mean to regulate the flow of water in order to grant a smooth passage for vessels between the river’s different levels.

photography by: Omri Westmark

The historic site is surrounded by a thick woodland that runs between the two aforementioned granite locks and the Tuckahoe Creek, along the route of the James River.

photography by: Omri Westmark

Although hardly a real hike, this deep forest trail offers a refreshing break from the excruciating Virginian Sun during the summertime, and also an occasional glimpse of the historically significant canal.

photography by: Omri Westmark

One of the trail’s highlights is a canal junction, where vessel traffic was diverted to the lock, so the power feeder canal can be utilized for the Pump House’s power generation.

photography by: Omri Westmark