In an era where one can travel to the other side of the globe in mere hours, it seems as though unexplored territories no longer exist. While the previous statement holds true almost invariably, there are still some places whose sheer remoteness insulate them from the rest of the world even today. Whether it is the lack of infrastructure, their hostile environment or a physical barrier like a forest, ocean or a mountain range, the following 10 oddities have been retaining their isolation amid our ever-increasing connectivity.

With roughly one person per square mile, the Sahara Desert is among the world’s most sparsely populated areas. After all, the excruciating heat coupled with the lack of precipitation make any kind of human habitation extremely challenging. Nestled within the sunbaked Tagant Plateau in central Mauritania is an oasis that not only managed to survive, but also to thrive amid these harsh weather conditions.

Tichit (sometimes referred to as Tichitt) is a semi-deserted townlet with around 5,000 residents, which can trace its origins back to as early as 2000 BC, making it the oldest extant village in West Africa.

In spite of its somewhat unassuming present, this isolated community was once the prosperous epicenter of the region’s ample salt trade. It was here that massive amounts of halite were mined and loaded onto camel caravans destined to various locations across the continent. As soon as camels were replaced by steamboats and trains, though, Tichit lost most of its importance, becoming a shadow of its former-self.

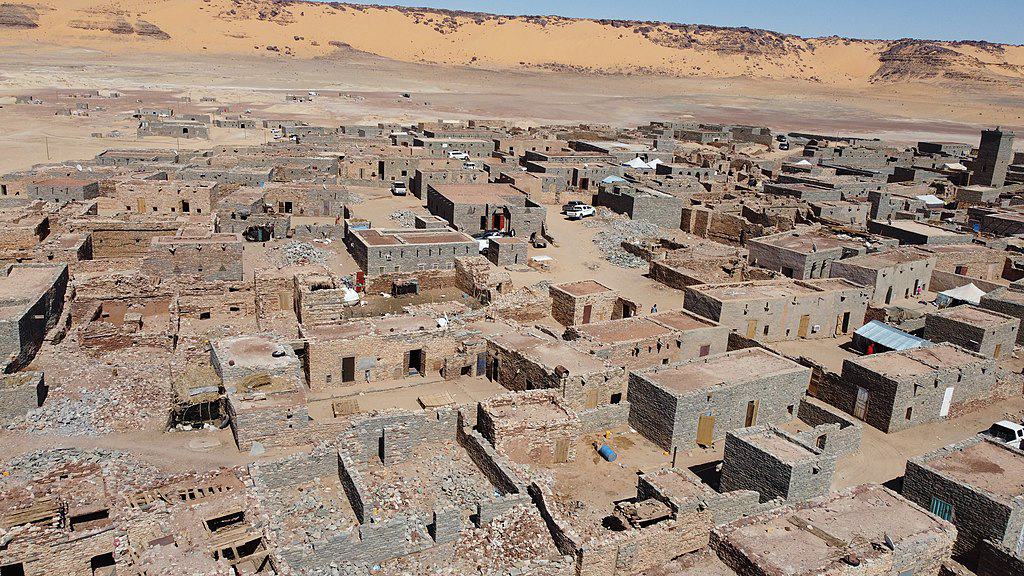

As of today, the locals’ main livelihood revolves around date farming and livestock husbandry, while modern amenities remain notably absent in the day-to-day life. Nevertheless, what Tichit lacks in contemporary comforts, it makes up for in unique architectural style as most of the houses here were built using colorful stones and mud.

The village is connected to the rest of the country solely by an unpaved runway and a single 200-kilometer-long dirt road leading to the regional capital, Tidjikja.

The haphazardly-scattered houses of Tichit, Mauritania

photography by: Mohamed Tar/ Wikimedia Commons

While Russia is the 9th most populous country in the world with more than 145 million residents, the overwhelming majority of the population is concentrated within its European provinces, leaving most of its territory exceedingly empty.

Tucked away in the far reaches of Siberia, Ayon (Айон) proudly contends for the dubious title of being the country’s most remote settlement. Home to a measly 200 people, the hamlet is situated on the shores of an island with which it shares its name, a part of the Chukotka Autonomous Okrug, the easternmost federal subject of Russia.

The faraway island has been continuously inhabited for nearly two millennia by the local Chukchi tribe, whose sole bread and butter was and still is reindeer herding. Due to the sheer remoteness of this landmass, the indigenous islanders have been contacted by outside visitors for the first time only in 1646.

Up until the 1940’s, the island’s lone settlement, Ayon, was inhabited only during the short summer season, turning into a permanent village by the Soviets who sought to collectivize the local reindeer industry. While nowadays, the hamlet is not as isolated as it once was, the only way to get there is either by a chopper or a 120-kilometer-long winter road over the frozen waters, through which Ayon gets the bulk of its supplies.

The Russian village of Ayon, Chaunsky District, Chukotka Autonomous Okrug

photography by: Ansgar Walk/ Wikimedia Commons

If Greenland, the world’s largest island, was an independent nation, it would be the most sparsely inhabited country by a large margin with an average density of only 0.14 people per square kilometer. Unsurprisingly so, this frigid place is home to some of the most isolated communities in our planet.

Among them one can find Siorapaluk (aka Hiurapaluk), the northernmost settlement in Greenland, located less than 1,400 kilometers from the North Pole. With bone-chilling temperatures nearly all year round, it is no wonder that the hamlet’s population fluctuates between 90 to 40 residents, most of whom are the descendants of Inughuit tribes who migrated from Canada in the late 19th century.

In the absence of arable lands, villagers resort to fishing and hunting for survival amid the extreme climate. Despite its miniscule size, Siorapaluk boasts its own power plant, grocery store, satellite connection, telephone service as well as a church which also serves as a school and public library.

But make no mistake, regardless of the surprisingly long list of present-day amenities, the small village is one of only few places across the island where the Inuit’s traditional way of life is well-preserved. Visitors who wish to explore this distant, yet authentic place will find it extremely difficult to get here, as the settlement is accessible from Qaanaaq exclusively by a helicopter service, dog sleds during wintertime and a boat ride throughout the short summers.

The hamlet of Siorapaluk, Greenland during the winter

photography by: National Snow and Ice Data Center/ Flickr

With 97.3 percent of its territory covered by the Amazonian jungles, Suriname is the world’s most forested country, acting as a one big oxygen factory. As a result, the bulk of the population huddles along the coast, most notably in the capital, Paramaribo, where nearly half of all Surinamese live.

The more south one goes, the more sparsely inhabited the area becomes, so much so in fact, that beyond a certain point, the national road network ceases to exist. Instead of highways, though, this vast area is crisscrossed by multiple rivers, where vehicles are replaced by boats and canoes.

The mid-forest riverbanks throughout Suriname’s largest district, Sipaliwini, are dotted with dozens of hamlets, and while each and every single one of them is extremely remote, it is Pelelu Tepu which truly reigns supreme in that realm.

Established in the mid-1960’s by the Dutch colonial administration as well as Christian missioners from the US, the village faced significant challenges throughout its relatively brief existence, becoming embroiled in a nationwide civil war in the 1980’s, during which hundreds of villagers fled to exile in neighboring countries.

Fortunately though, Pelelu Tepu has since recovered and now boasts more than 600 residents, the majority of whom are Tiriyó, an Amerindian ethnic group. In spite of its far-flung whereabouts, the settlement has its own school, solar-based electricity supply and since 2001, also a training center for shamans, whose healing prowess often compensate for the absence of conventional medicine across the region.

Pelelu Tepu’s main square

photography by: De Boodschap/ Wikimedia Commons

In 2023, India’s population reached 1.428 billion, thus dethroning China as the world’s most populous nation. Excluding micro-states like Monaco or San Marino, India is also among the most-densely-inhabited countries across the globe, glutted with people wherever one looks.

That is, unless you are talking about India’s mountainous provinces. With an average altitude of more than 4,500 meters, sustaining large-scale human habitation in this part of the country is virtually unfeasible. Therefore, rather than overcrowded cities, the alpine fringes of India’s region of Ladakh are peppered with pocket-sized hamlets, some of which are still cut-off from the national system of roads.

Perhaps the most isolated community of all is a tiny village by the name of Rumbak, home to a meager 250 residents who nowadays, make ends meet by catering to the occasional mountaineers who visit the area. The smattering of whitewashed mud houses here are adorned with wooden windows and colorful prayer flags that reflect the place’s centuries-old Buddhist traditions.

Nestled along a valley that bears its name, the hamlet is part of Hemis National Park, a protected enclave where some of the planet’s most endangered species are sheltered from harm’s way. In fact, Rumbak is often dubbed “The Snow-Leopard Capital of the World” for its unusually large number of these rare animals, whose local population nearly matches that of their human counterparts.

To get here, one would have to go to great lengths, literally so. From the nearest drivable road in the village of Zinchan, it is about 4-5 hours of trekking across the ravine.

One of Rumbak’s whitewashed buildings

photography by: Tsogskor/ Wikimedia Commons

Steeped in the vast expanses of the Pacific Ocean, French Polynesia comprises 121 islands and atolls scattered across a stretch of water spanning more than 2,000 kilometers. While the archipelago is largely synonymous with the vacationer-infested resorts of Tahiti and Bora Bora, there is far more to this overseas collectivity than just its high-end tourist attractions.

The southernmost point of French Polynesia, Rapa Iti is indisputably the territory’s most remote landmass, located more than 500 kilometers away from the nearest inhabited place, Raivavae Island. According to the last census, only 507 people call this speck of land home, all of whom live along Haurei Bay, in one of Rapa Iti’s three settlements, Ahurei, Tukou and Area.

There were times, however, when Rapa Iti far exceeded its current peripheral status. In fact, for a couple of centuries or so, this forested and mountainous island boasted its own kingdom, while supporting over 2,000 inhabitants.

Sadly, Little Rapa’s prime days came to a bitter end in the early 19th century, when the nascent contact with the many European explorers who frequented its shores resulted in the outbreak of diseases that decimated nearly three quarters of the entire population. What little remained of this once prosperous community was then pulverized by Peruvian slave masters who raided the kingdom and kidnapped dozens of islanders to forcefully work in guano mining within the Chincha Islands.

Since then, Rapans have managed to recover from the precipice of extinction against all odds, and thanks to the island’s sheer isolation, still keep their own language, cultural traditions and cuisine. In the absence of an airport, whoever wishes to explore Rapa Iti will have to hitch a ride on one of the monthly cargo vessels that carries supplies from further afield.

Ahurei Bay in Rapa Iti

photography by: Sardon/ Wikimedia Commons

In the frozen wasteland that is Antarctica, humans are as rare as pandas and rhinos, after all, temperatures here can plummet to a staggering -80°C at its lowest. To the surprise of many, though, the barren continent is not as empty as you might assume.

Tucked away on the shores of King George Island, the largest among the South Shetland Islands, Villa Las Estrellas (Hamlet of the Stars) is one of only two civilian settlements across the entirety of Antarctica (along with the Argentinian-administered Esperanza Base). Part of President Eduardo Frei Montalva Base, the village was originally established by Pinochet’s Chile in 1984 as the government sought to reinforce its territorial claims over the Antarctic region it calls Antártica Chilena.

The village’s population of scientists, military personnel and their families fluctuates between 150 at the summer to as little as 80 in the frigid winter season, during which the sun is rarely in plain sight. To mitigate these harsh conditions, Villa Las Estrellas enjoys a surprisingly hefty number of amenities for such a small place.

It is here that one can find a modern hospital with one doctor and one nurse, a post office, a bank, an ample sports center and a hilltop church. In addition, residents also have internet access alongside television, radio, mobile and telephone services. Up until 2018, Villa Las Estrellas also had a school where a pair of teachers were tasked with educating the hamlet’s handful of children. The schoolhouse was forced to close its doors due to maintenance issues, albeit there are plans reopen it in the near future.

While the village is one-kilometer shy of a full-fledged airport, there are no regular flights that connect it with the rest of the world, but rather a couple of charter flights from Punta Arenas every now and then. Plucky visitors who do manage to make the long journey will come across a small hostel, a souvenir shop and perhaps most strikingly, a winter-sky full of stars, hence the hamlet’s name.

The snow-covered village of Villa Las Estrellas, Antarctica

photography by: Mefisto29/ Wikimedia Commons

Well before the advent of global shipping routes and modern navigation tools, merchant ships used to embark on a perilous odyssey across the open ocean in search of valuable goods. Conspicuous by its unusual turn of events, the HMS Bounty was a 90 feet long collier sent in 1787 to Tahiti on behalf of the British Crown to transport breadfruits all the way to the West Indies.

In the wake of incessant bickering between the crew members, a mutiny broke out as the ship sailed back with its precious cargo. Following a series of skirmishes on board, the mutineers seized control of the vessel and rerouted it to the Pitcairn Islands, where the 8 English crewmen, 6 Tahitian men and 11 Tahitian women settled as part of their plan to evade the British authorities.

In the years that followed, a deadly dispute claimed the life of all Tahitian men and 7 English mutineers, yet the descendants of the original settlers established a biracial community that has persisted to date.

Fast forward to today, the 4-island archipelago is now a British overseas territory, whose sole settlement and capital is home to a measly 47 people, making it the least populated national entity in the world. Situated on Pitcairn Island (not be confused with the Pitcairn Islands), the tiny hamlet is named after John Adams, the last English mutineer who lived here.

Whilst Adamstown is a far cry from nearly every modern capital, its residents enjoy basic amenities such as electricity, healthcare and postal service, internet access, television, radio, a church and even a police station. Given their sheer isolation, the islanders developed their own unique culture and language (Pitkern), in which English and Tahitian are blended together.

As the remote archipelago lacks an airport, it is among the planet’s most difficult to access places. Be that as it may, adventurists who have enough money and time can get here on board the MV Silver Supporter, Pitcairn’s freight vessel which goes back and forth between Adamstown and Mangareva Island in French Polynesia.

Adamstown’s houses dotting the verdant coast of Pitcairn Island

photography by: doublecnz/ Wikimedia Commons

Lying less than 1,500 kilometers off the Antarctic coast, the island of South Georgia is a desolate speck of land, whose freezing temperatures and remoteness make it a hostile place to live all year round. It is for this reason that up until the turn of the 20th century, this frigid hellscape remained uninhabited.

In 1904, Norwegian seafarer Carl Anton Larsen established the island’s first permanent outpost, a whaling station entitled Grytviken. In its heyday, roughly 300 men called the townlet home, partaking in Grytviken’s ample whaling industry. It was here that the blubber, bones and meat of whales and seals were processed into oil and provender for shipment to various parts of the globe.

Nonetheless, following years of excessive haunting, the surrounding waters were depleted of most of their marine life, rendering the practice economically unfeasible. By December 1966, the station ceased its operation and was left abandoned, quickly descending into a state of disrepair.

In the aftermath of its demise, King Edward Point, a British research station located half a kilometer to the east along an eponymous cove, remained the lone settlement throughout the entire island. Founded in 1909 as the residence of the British officer who administrated the landmass, the hamlet was expanded in 1925 to include a marine laboratory for scientific experiments.

The smattering of houses that is King Edward Point has a winter population of a mere 12, a figure that nearly doubles every summer when additional staff arrives to reenforce the existing personnel. Curiously, since the pint-sized village also serves as the capital of UK’s Overseas Territory of South Georgia and the South Sandwich Islands, it is considered as the smallest capital of any national jurisdiction anywhere in the world.

Each year, several Antarctic expeditions frequent the island, exploring Grytviken’s rusting facilities where whale oil was once manufactured. Littered with whale bones, the abandoned town boasts a museum and church that operate intermittently, and where intrepid travelers huddle to have a glimpse of the place’s bygone era.

King Edward Point’s small cluster of buildings

photography by: Liam Quinn/ Wikimedia Commons

Roughly halfway between Africa and South America, in the south Atlantic Ocean, lies a settlement so remote that getting there can be as challenging as traveling to the outer space. Comprises a cluster of several volcanic islands and islets, Tristan da Cunha is part of the British overseas territory of Saint Helena, Ascension and Tristan da Cunha.

Owing its name to the Portuguese explorer who discovered them in 1506, the islands were first colonized only in the 19th century, as Britain sought to counterbalance other global powers such as France and the then newly established United States. With no other landmass in sight, Tristan da Cunha played a major economic and strategic role for an extended period of time.

However, the territory’s days of relative importance were short lived as the introduction of steam ships coupled with the opening of the Suez Canal in 1869 meant that vessels traveling from Asia to Europe or vice versa no longer had to stop on its shores for shelter and procurement of supplies. Since then, the archipelago has slowly but steadily descended into a complete obscurity, becoming more isolated with every passing year.

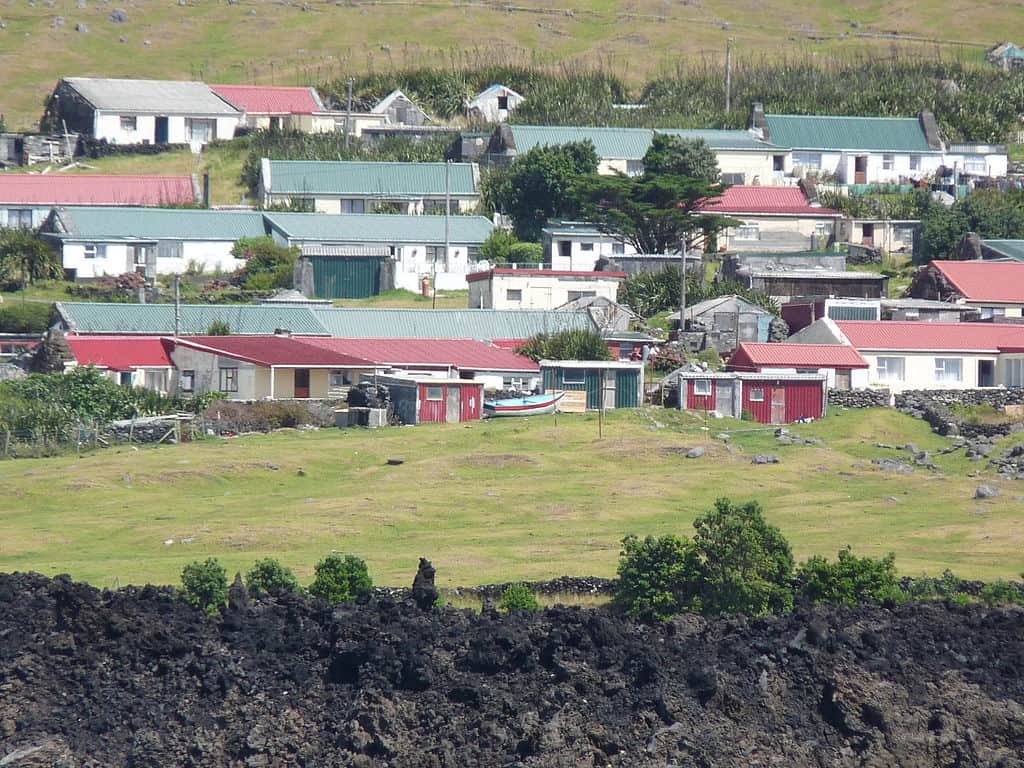

To the untrained eye, Tristan da Cunha’s sole settlement might look like a typical Scottish village, but as the “Welcome to the Remotest Island” sign that greets newcomers proudly contends, it is anything but usual. Nestled on the northern coast of the main island, Edinburgh of the Seven Seas is home to 250 people, for whom the townlet offers a surprisingly long list of comforts and services.

Not only do the islanders have their own post office, public hospital, three churches, grocery store and a graveyard, but also a bustling café and a typical English pub named Albatross Bar, where locals mingle from noon to dusk.

Given the islands’ far-flung location, adventurists who wish to explore this last frontier will have to plan their trip months ahead of time. In fact, the only viable way of visiting Tristan da Cunha is by boarding one of the 9-10 annual trips made by cargo vessels from Cape-Town. With choppy waters along the way, the arduous journey can take up to a whopping 10 days. Nonetheless, the rough seas aren’t the only obstacle as any visitor must first be approved by the island council (for more details visit the islands’ official website).

The world’s most isolated settlement - Edinburgh of the Seven Seas, Tristan da Cunha

photography by: michael clarke stuff/ Wikimedia Commons