History tells stories of cities sinking into the sea and towns being swallowed up by natural disasters but the idea of a municipality upping sticks to move just a few kilometres down the road is a relatively rare phenomenon. Yet such is the case in Kiruna, Sweden’s northernmost city, located 200km above the Arctic circle. Home to the world’s largest iron ore mine and built in 1900 to house its workers, mining-related subsidence now requires the city centre to migrate three kilometres east, along with one third of the urban population. While the move began a decade ago, the logistical challenges inherent in such an endeavour mean that the town is now in limbo for at least the next decade. The sharp contrast between the slow dismantling and demolition of Old Kiruna and the rising state-of-the-art glass and steel structures of New Kiruna represents the price of progress in a place where economic co-dependency is simply an unavoidable fact of life.

The presence of iron ore in the Kiirunvaara mountain was known by the indigenous Sámi population for centuries but the commercialisation of these natural mineral resources only became possible with the construction of a railway line connecting the ports of Narvik on the Norwegian Sea and Luleå on the Baltic Sea.

The project was initially started by the Northern Europe Railway Company in 1884 but by 1888, with the line only going as far as Malmberget, the English company went bankrupt and had to sell the railway to the Swedish state for 8 million Swedish crowns (US$0.8 million), half their initial investment. After significantly rebuilding the railway and under pressure from the newly formed mining company Luossavaara-Kiirunavaara Aktiebolag (LKAB), the line finally came to Kiruna on 15 October 1899 and the Swedish and Norwegian sections were joined on 15 November 1902.

Becoming known as the “Iron Ore line”, the new railway was essential for LKAB: it was now possible for them to begin mining because the output could be transported to the ice-free port of Narvik in Norway for international trade and to Luleå to serve Baltic customers.

Once the train line was up and running, LKAB’s first managing director, Hjalmar Lundbohm, began to develop the town of Kiruna close to the mine. The town’s name pays homage to the local fauna: it means rock ptarmigan in Sámi and Finnish, a medium-sized snow grouse native to the region.

Given the present-day requirement to relocate, hindsight might give rise to questions about the decision to build in such proximity to the mine but at the time, the location seemed logical as the nearby mountains provided protection from Arctic winds. Lundbohm was passionate about the development of the so-called “model company town” and following his death in 1926, he was buried beside the Kiruna church, the only person ever interred there.

As LKAB expanded their operations deep below the surface, Kiirunavaara and its sister mine in Malmberget (in Gällivare) became the two largest and most modern underground iron ore mines in the world, producing 80% of the EU’s supply. While the increased activity boosted the town’s economy, it was a double-edged sword; as the inhabitant’s incomes rose, their homes and businesses were slowly sinking into the ground, with noticeable cracks appearing in populated areas.

Something needed to be done and in 2004 a radical plan, involving contributions from architects and sociologists, was made to move the city. The initial new location, proposed in 2007, was northwest, to the foot of the Luossavaara mountain. This was eventually rejected in 2010, when the city council decided it would be better to move the town eastwards, in the direction of Tuolluvaara.

The physical process of moving to this new site began in 2013, with the closing of the railway station on 31st August. A temporary railway station 2 kilometres from the new city centre has been operating since then, with free shuttle buses between it and both the old and new towns running regularly all year around.

While the construction of new buildings is never easy, it is a comparatively simple undertaking compared to the logistical challenge of moving 21 heritage buildings in their entirety. Of the ones that have been moved to date, most have been lifted onto trucks and transported on closed roads to their new site, while some have had to be partially dismantled and reconstructed.

All 600 tonnes of the Gothic revival-style Kiruna church are set to be moved by trailers in 2026, a plan that will require experienced labour to ensure the 1912 building, once voted the most beautiful in Sweden, survives the journey intact.

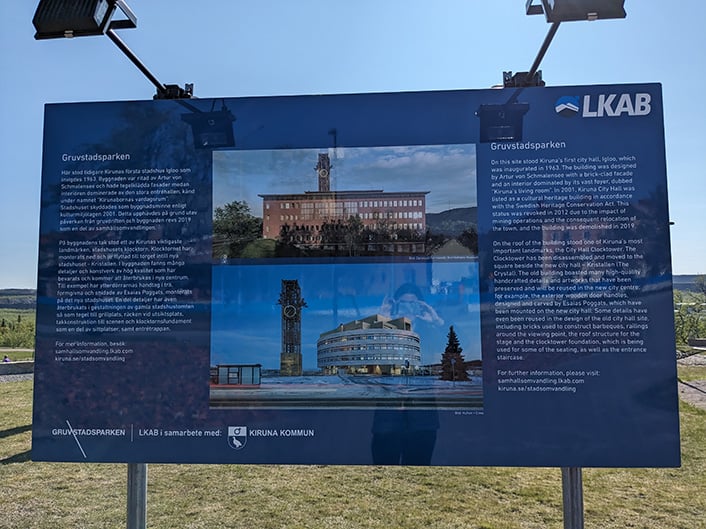

While it might have been hard initially for residents to imagine these historic buildings in a different location, since 2018 the new city centre has had a great example of how old can be successfully interwoven with new. The huge town hall, “Kristallen” or “The Crystal” is a striking circular gold and glass edifice, built beside the relocated 1963 iron clock tower.

The contrast between the shining new communal construction and the dark tones of the eight-tonne tower is somehow complementary and marks the beginning of Kiruna’s new skyline. The old town did not really have a proper centre so Kristallen seeks to provide that, with designated areas for hosting both internal and external events.

The modern design of the new town, with an extensive shopping centre, better public amenities and a focus on more environmentally sustainable housing, also aims to help retain its younger residents and attract tourists in search of Aurora Borealis or the famed Arctic fauna. While the new city is still very much under construction, it is clear that it is starting to take on its own identity, albeit with strong links to its predecessor down the road.

All of this change does not come without costs – and in Kiruna, the price tag is significant. Because the town’s relocation is a direct result of mining activity, LKAB are responsible for paying for the move and so far, it is estimated that their outgoings on the project total US$1.8 billion. They have a further US$1 billion in reserve for future infrastructure projects.

LKAB has always been closely linked to the Swedish state and has been fully state-owned since 1957, meaning that 75% of the funding for the relocation has come directly from the government. The majority of the rest comes from private investment companies and the remainder is subsidised by EU grants.

The company is profitable (around US$2 billion annually) and the move has been staggered, which eases the pressure slightly, but any disruption to iron ore production needs to be carefully monitored to ensure that profits remain sufficient to support this unprecedented upheaval.

The ambitious and modern new city centre

photography by: Sinéad Browne

The influence of the national government, the ultimate owners of the mine, has given rise to some issues with local authorities, who are directly affected by policy decisions made that are outside their control. An example of this is the pricing structure for the 6,000 residents (3,000 households) required to move: those who owned their own properties sold them for up to 125% of their value but prices have risen significantly since then, particularly for apartments, so some residents are struggling to afford a new home.

For those renting, new builds carry a higher rate and although this is capped at 25% of the old rate over eight years, this still puts significant financial pressure on the town’s population. There is also the looming threat of technology taking the place of workers in the mine, meaning that residents need to make some difficult decisions as to whether the move is financially viable.

This is compounded by the long-term nature of the relocation: while staggering the move makes sense for LKAB, it has resulted in some businesses being left without a premises for a number of years, ultimately causing them to close. An exploration of the old town reveals some shopfronts with closing signs dating back to 2018 and a proposed reopening date in a new location as far ahead as 2025; downtime that not many enterprises can afford.

A further consideration of the move is the emotional and cultural effect that it has on the local population. While reinstalling heritage buildings and even some street names is helping to mitigate this, it is hard for people to let go of attachments – symbolic buildings such as the former town hall have now been reduced to rubble and many childhood homes now live on in memory only.

The disruption also impacts the area’s rural residents; Sámi reindeer herders in the village of Gabna, already under threat from climate change, may have to find alternative routes as the construction work progresses. There is also a lurking feeling of unsettlement with the remaining two-thirds of residents, who may ultimately have to move if LKAB continues its operations after 2035.

The recent discovery of a huge deposit of rare earth metals, needed for electric vehicles, makes this increasingly likely. The location of the new city centre was carefully chosen but there are still inherent risks: in May 2020, an earthquake of approximately 4.9 moment magnitude was triggered in the region by mining operations.

All of this results in a fascinating symbiosis: without the mine, there is no town and without the town, there is no mine. Recognising this, the architects of the relocation are working to preserve as much of the community spirit as possible. Demolition sites that are currently cordoned off will become “Gruvstadsparken”; green spaces designed for social and cultural events.

Projects such as “Kiruna Forever”, showcasing work by architects, urban planners and artists involved in the move, can be viewed online, increasing international interest in the area. The aforementioned financial and design challenges are not insurmountable and amidst all of the uncertainty and upheaval, the publicity from such an extensive endeavour has the eyes of the world on Kiruna, a city trying to escape the narrative of becoming a cautionary tale.

Gruvstadsparken placard showing the old town hall

photography by: Sinéad Browne